The 1979 disappearance of Etan Patz helped catalyze a national missing-children's movement. The 6-year-old was one of the first children whose disappearance was publicized in what became a high-profile way: on milk cartons. His case also ushered in an age of parental anxiety.

A newspaper with a photograph of Etan Patz is seen May 28, 2012, at a makeshift memorial in the SoHo neighborhood of New York, where Patz lived before his disappearance on May 25, 1979.

After a decadeslong investigation, former New York City convenience store clerk Pedro Hernandez was arrested in 2012. He was convicted of murder and kidnapping in 2017 and sentenced to 25 years to life in prison.

On July 21, a federal appeals court overturned the verdict and ordered a new trial for Hernandez, now 64.

Here's what to know about Etan's disappearance and the prosecution:

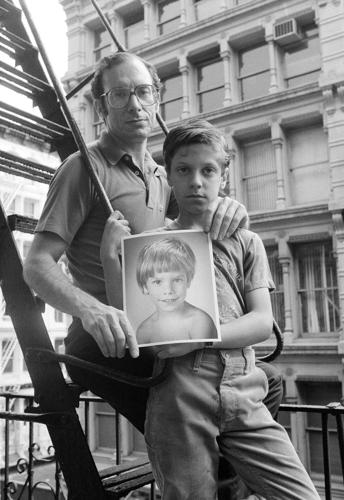

Stanley Patz and his son Ari poses with a photo of his other son Etan on May 18, 1985, in New York. Etan Patz disappeared on the way to the school bus stop in 1979.

Boy vanishes

Etan disappeared while walking to his Manhattan school bus stop alone for the first time May 25, 1979, igniting an exhaustive search and helping to make missing children a national cause in the United States.

People are also reading…

The anniversary of his disappearance became National Missing Children's Day. His parents helped press for new laws that established a national hotline and made it easier for law enforcement agencies to share information about missing children.

The movement grew after the 1981 kidnapping and killing of 6-year-old Adam Walsh in Florida. Frightened parents soon stopped letting children walk alone to school and play unsupervised in their neighborhoods.

A photograph of Etan Patz hangs on an angel figurine May 28, 2012, part of a makeshift memorial in the SoHo neighborhood of New York.

Probe spans decades

Etan's body was never found, but his family had him legally declared dead in 2001.

The investigation spanned decades and even reached Israel.

Hernandez worked at a convenience store in Etan's neighborhood, and police noted meeting him among many people they encountered while searching. He wasn't a suspect until 2012, when police got a tip that Hernandez, then living in New Jersey, once spoke to a relative about killing a boy in New York City.

Disputed confession

Pedro Hernandez appears Nov. 15, 2012, in Manhattan criminal court in New York.

There was no physical evidence against Hernandez, but police said that during a seven-hour interrogation he confessed to attacking Etan.

In recorded statements, Hernandez tranquilly recounted offering soda to entice Etan into the basement of the convenience store where Hernandez was then a teenage stock clerk. Hernandez said he choked Etan, put the still-alive boy into a plastic bag and a box and left the box in an alley.

Hernandez's lawyers said the admissions were the false imaginings of a man with mental illness and a very low IQ.

The defense also urged jurors to consider another longtime suspect who dated a woman who sometimes walked Etan home from school. That man later was convicted of molesting boys in Pennsylvania. He told federal authorities about interacting with a child he was all but sure was Etan on the day the boy vanished. However, he was never criminally charged.

Prosecutors maintained that Hernandez's confessions were credible and suggested he faked or exaggerated symptoms of mental illness.

Stan Patz, father of missing 6-year-old Etan Patz, arrives Feb. 14, 2017, at Manhattan Supreme Court in New York, accompanied by Jennifer O'Connor, a juror in the first trial of Pedro Hernandez.

Appeals court ruling

In its July 21 ruling, a federal appeals court overturned Hernandez's conviction because of the original judge's response to a jury note during a 2017 trial.

The appeal revolved around the police interrogation that Hernandez underwent in 2012. Police said he initially confessed before they read him his rights. Hernandez was then given a legally required warning that his statements could be used against him in court, then repeated his admission on tape at least twice.

At the trial, the jury sent a note to the judge asking whether it should disregard the two recorded confessions if it concluded that the first one — given before the Miranda warning — was invalid. The judge answered "no." The appeals court ruled that the jury should have gotten a more thorough explanation of its options, which could have included disregarding all of the confessions.

The court ordered Hernandez to be released unless he received a new trial within "a reasonable period."

The 2017 trial was Hernandez's second; his first ended in a deadlocked jury in 2015.